Title: Front Projection for "2001: A Space Odyssey" by Herb A. Lightman

From: American Cinematographer

An incredibly bright image on a huge screen lends tremendous scope to a limitless subject and adds an extra dimension to the art of film making

Perhaps the most significant single technique utilized in M-G-M's "2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY" -considered in terms of its potential value to the film industry as a whole - is Stanley Kubrick's extensive use of a completely new departure in the application of front-projection for background transparencies.

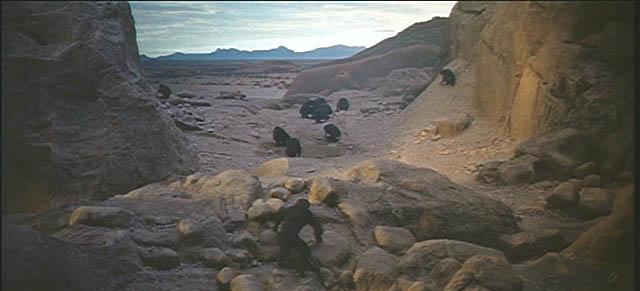

This advanced technology evolved out of the dramatic demands of his "Dawn of Man" prologue which called for hordes of ape-men to be shown against vast natural terrain backgrounds of primeval beauty. A perfect location in a remote area of Southwest Africa had been found and Kubrick was anxious to use this spectacular setting for his opening sequence.

"The geology in that area was completely different from anything else I'd seen," he explains. "The rocks ddn't look like 'Bible' rocks and they didn't look like 'Western' rocks. They were really quite unique."

To capture this setting on film the way he envisioned it there were several options open to him. The first, most obviously, would have been to take a large cast and crew on location to the actual site. However, aside from the enormous cost involved, the company would most likely have found itself at the mercy of inclement and ever-changing weather.

Another obvious alternative would have been the use of a painted backdrop, which, in this case, would have had to be 40 feet high and 110 feet wide. The main drawback was not the size, but rather the fact that such backdrops all too often look like exactly what they are.

In theory, the blue-screen matting system could have been used, or even a king-size adaptation of the standard rear-projection process method. In actual practice, however, each of these approaches, applied on such a vast scale, might not have produced quite the illusion of reality which the director hoped to achieve.

He elected, instead, to use front-projection on a scale never before attempted. The front-projection concept is not, in itself, new. The method has, in fact, been in practical use for several years, mainly by still photographers and in television studios. It had not, however, up until now, been used to any great extent In the motion picture industry.

The largest format utilized to date had been a 4 x 5-inch Ektachrome transparency, but it was felt that the grand-scale requirements of this particular space epic would demand an even larger transparency.

"I had made a test using a 4 x 5 still and it was almost good enough, so I was positive that with an 8 x 10 the effect would be perfect," Kubrick comments. "The trickiest part would be balancing the foreground illumination to match the intensity of the front-projected background. Now that it's over I'm convinced that if a still transparency is to be used for the background scene an 8 x 10 is essential, because if you dont have a surplus of resolution you are going to get a degradation, of the projected background image."

The only drawback at the time was that there existed no such device as an 8 x 10 projector - let alone one powerful enough to throw a bright image across 90 feet of foreground area onto a screen 110 feet wide. Working in close cooperation with M-G-M Special Effects Supervisor Tom Howard, Kubrick set about building his own super-powerful 8 x 10 projector, with a condenser pack 18 inches thick made up of condensers from standard 8 x 10 enlargers. The most powerful water-cooled arc available was employed as a light source and it was necessary to use slides of heat-resistant glass in front of the condensers in order to prevent the heat from peeling the magenta layer of emulsion right off of the transparency. At least six of the rear condensers cracked because of the heat during the filming, but this was usually due to a draft of cold air hitting the projector when someone opened the door of the sound stage while the projector was operating.

On the set of "2001: A Space Odyssey," producer-director Stanley Kubrick uses binoculars to check fine focus on the vast front-projection screen. Special 3M material reflects 100 times the light falling upon the screen, provided that projector and film camera lenses are aligned on precisely the same axis. Kubrick wanted to use an 8x10 transparency for maximum sharpness, found there was no projector for it in existence, built his own.

In order to conserve the transparencies as much as possible, the projector was only turned on during the one to five minutes at a time needed to make an actual take with the camera. For purposes of aligning the equipment a reject plate was used. Since any dust or dirt appearing on the surface of the plate would be magnfred on the giant screen many times and become clearly apparent, the most careful precautions had to be taken. Anti-static devices were used and the plates were loaded under 'antiseptic" conditions. The operator who loaded plates into the projector used editing gloves, and even wore a surgical mask so that his breath would not fog the mirror.

In aligning the camera-projector configuration for front-projection the projector was set up at right angles to the camera with the projected image beamed onto a partially-silvered 36-inch-wide mirror mounted at a 45 degree angIe about eight inches in front of the camera lens. The camera photographed through the mirror, the projected image onto the screen. A heavy steel rig with micrometer adjustment was engineered to assure the very critical alignment between camera and projector in order that there would be no possibility of 'fringing.' A nodal camera head made it possible to pan across the mirror in scenes where the camera lens was fielding a composition that included less than the full screen.

As astronaut enters a different time space dimension near Jupiter, bright colors flash across his visor. These were actually reflections from the pod instrument panel, filmed at 12 frames-per-second.

A key requirement in front-projection is that the camera and projector be so precisely aligned that, in terms of physics, the projected light source and the center of the camera lens are located at the same point. Or, in more graphic terms, as if the light source were inside the camera. This is essential because of the peculiar uni-directional reflectivity of the screen material used, which produces a phenomenal gain in brilliance - but only when projected light is reflected directly back to its source.

The surfacing material used for the giant screen was a special 3M fabric coated with very tiny mirrored beads of glass. It has the incredible capability of reflecting 100 times the amount of light that is projected onto it, so that, theoretically, if the light falling onto the screen gave an incident light reading of 1 foot-candle, the light reflected back to the camera would measure 100 foot-candles.

This special lenticular 3M material comes in rolls and an effort was made to surface the screen by mounting it in 100-foot strips. However, because of a slight variation in reflectivity between rolls, seams were frequently visible under projected light. An attempt to match strips exactly proved unsuccessful, so the material was finally torn into small, jagged, irregular shapes which were mounted in a "camouflage" mosaic, shape on top of shape, so that there was no longer any visible variation in reflectivity.

Frame blow-up from the "Dawn of Man" prologue to "2001" indicates the scope of background that can be achieved on the sound stage . Kubrick recommends the 8x10 size transparency for maximum sharpness. M-G-M is now building a 65mm front projector with a frame 20 sprocket holes wide so that moving backgrounds on a large scale can be used.

It is natural that certain obvious questions should come to mind in relation to the front-projection technique.

Firstly, since the projected image is falling upon the foreground subject as well as upon the screen in the background, why is that projected image not at least partially visible spilling onto the foreground subject - particularly in view of the fact that such a subject is much closer to the camera than the background screen? The answer is that exposure of the entire scene must be gauged to the extremely brilliant image reflected from the screen and which, because of the incredible reflectivity of the 3M screen material, is 100 times brighter than any light image reflected from the foreground subject. This would pertain even if the foreground subject were a person wearing a silver suit; he would still show up on the film as a black figure silhouetted against the brilliant image. Even though the faint image falling upon the foreground subject might be dimly visible to someone present on the set, it would be too faint for the film to "see" - because there simply does not exist an emulsion with a wide enough latitude to accommodate such an extreme brightness contrast range. In addition, a tremendous amount of light is needed to balance the foreground subject with the extremely bright image reflected from the screen. This light would effectively "wash out" any residue of front-projected image falling upon the foreground subject.

The second question that might logically be asked is: Why aren't the shadows of foreground objects visible on the background screen? The answer is that, since the light source and the camera lens are precisely aligned on a common axis, the foreground subject exactly 'fits' its own shadow, covering it completely. So perfect is the match that even if a front-projected closeup were made of a girl with her hair blowing in the wind, each individual hair would completely cover, and therefore "hide," its own shadow.

In order to photograph the magnificent vistas used as backgrounds for the "Dawn of Man" sequence, Kubrick had three still camera crews operating in Southwest Africa for several months with 8 x 10 view cameras. In addition to the spectacular terrain itself, the dramatic cloud formations evoke images of an Earth millions of years younger, still in the lingering spasms of creative convulsion, a sphere of savage and violent beauty.

"This sequence was especially well suited to the use of front-projection because all of the backgrounds were desert scenes in which nothing had to move," says Kubrick. "Our location still photographers were able to wait for just the right moment and shoot a scene in light that would remain exactly that way for perhaps only five minutes out of a whole day. But on the stage we could shoot the sequence at our own pace in constant light of the type you could never maintain on location, no matter how much money you might spend."

In addition to the "Dawn of Man" prologue, the front-projection system was used to establish scenes of the astronauts walking on the lunar surface. Onto the background screen was projected a photograph of a miniature set representing the, vast American Moon-base within the crater CIavius. The foreground action shows the astronauts amid huge lunar rocks that apparently tower above the base. An artist's conception of the final breath-taking scene appears in full color on the cover of this issue of AMERICAN CINEMATOGRAPHER.

The main lighting key of the front-projected sequences was geared to the amount of iight that could be poured on to reflect from the background screen. The lighting of the foreground and the actors moving in that area was then keyed to balance naturally with that of the background scene.

An enormous amount of basic light was needed to produce the "cloudy bright" simulated daylight illumination for the foreground areas in the "Dawn of Man" sequence, and this was provided by covering almost the entire ceiling of the sound stage with a total of 1500 RFL-2 lamps.

"Each of these lamps had its own individual switch so that we could maintain very delicate control of the foreground lighting," Kubrick points out. "This was necessary not only in order to match it with the background lighting, but also because the height of the set varied. In some areas the 'hills' were closer to the ceiling than the surrounding terrain. The individual switches made it possible to turn off any one light all by itself and to literally shape the light to the contours of the set. We could do this very, very quickly and with the greatest flexibility."

While Brute arcs with straw-colored gels in front of them were used to provide a hint of modeling and relieve the basically flat effect, no attempt was made to create a strong point source suggesting direct sunlight.

"There's simply no really effective way to realistically simulate a single light source when you're shooting such a huge area In a high lighting key," Kubrick explains, "but if you're shooting for an effect of cloudy weather or spotty sunlight, you can match it perfectly to the background. And that kind of lighting looks better anyway, in my opinion, than full, direct, 'Kodak Brownie' sunlight."

The ghostly night scenes in the "Dawn of Man" sequence were photographed by using basically the same techniques that are routinely employed for shooting day-for-night exteriors in the true outdoors - namely, a couple of stops of under-exposure and printing through a light blue filter.

One stunnng effect that invariably brings gasps from the audience was achieved quite unexpectedly and may be regarded as a sort of "bonus" to the production. During the prologue a lithe leopard is seen moving among the rocks. As the big cat turns its head full into camera its eyes seem literally to light up with a brilliant, fluorescent orange glow. The impact is startling.

"A happy accident," shrugs Kubrick. "I can only conjecture that the cat's eyes must contain some substance having a reflectivity similar to that of the 3M material used on our screen, because the eyes picked up the front-projected light and reflected it almost as brightly as the screen itself.''

In order to utilize the full scope of the front-projection screen, the normal shooting combination paired a 75mm lens on the film camera with a 14-inch lens on the 8 x 10 projector. However, it was possible, by "cheating" a bit, to record scenes with an even wider scope. This was accomplished by using a 50mm lens on the camera and extending the sides of the composition beyond the limits of the screen with foreground elements such as a boulder or a river bank.

In pod-bay set , Kubrick mulls one of the many thousands of technical problems that beset him during production of space epic.

There is no doubt that the superlative quality of the front-projection sequences in '2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY" will lead to a widespread adoption of the technique within the film industry. "In my opinion it will revolutionize what we used to call 'transparency photography' because of its great flexibility and scope," comments M-G-M Post-production Administrator Merle Chamberlin. "Because it affords the capability of projecting a sharp, clear background onto such a huge screen, it will be possible to achieve tremendous production value at a relatively low cost. You can create almost any locale quite realistically right on the sound stage, and march a whole army through it if you choose - in one door of the stage and out the other."

Already the process is being used in the production of another M-G-M super-spectacle, "WHERE EAGLES DARE," which is currently shooting in London, and Special Effects expert Tom Howard is adapting it to the use of moving backgrounds by devising a special 65mm motion picture movement that will accommodate a frame 20 sprocket holes wide. This movement will transport the film horizontally (much in the manner of Vista-Vision) and will make possible the front-projection of a very large and clear motion picture scene to be used as a background.

If for no other reason than this, the production of '2001' might be considered a cinematic milestone - but there are a great many more reasons!